Earlier this year Westchester Group Investment Management (WGIM) bought roughly 50,000 acres from Gaylon Lawrence, Jr. (Lawrence Group – LG). An article by Agri Investor suggests the property was bought for $4,500-$5,000 an acre. Further, it quotes a source saying rents in the area are $150 per acre. Even if WGIM can move rents to $200 an acre that puts cap rates at between 3% and 4.4%. For institutional buyers like WGIM and institutional sized buyers like LG (I’ll refer to both as institutions from here on) these transactions will continue to make sense, but farmers will continue to find deals despite being priced out of other transactions. For those in neither camp hoping to innovate, creating value by chipping away at inefficiency without outrunning the market where it stands will be the key.

Low Returns for everyone?

How can an investment at 3% be justified in a world where typical Venture capital returns are more like 20%? With commodities in a protracted cyclical downturn can rents be sustained at this level? How can farmers compete with funds who are willing to buy at these rates and at this scale?

The Two Land Markets

The row crop industry is highly inefficient – information remains highly localized. Land sales or tenant changes often remain unknown until months afterward. Further, details about leasing or transaction price remain speculative. The best information available for these numbers comes from land auctions and institutional land rent rolls. However, both of these sources are likely to be on the high side of the market.

Institutions deal in this space, the high side. While they may have individual transactions which are better than others, the majority of their purchases will be on the higher side of the market. They are willing to pay a premium for high quality land in large quantities because it works for their business model. Institutions have recently raised massive funds which they have to get deployed. The only way for them to put their capital to work is to purchase land in large quantities. The only way for them to purchase large quantities is at a premium.

With several large institutions all vying for a few big deals a year the underlying structure on the larger side of the land market has changed. A price floor has been created by the flow of money into the market. Instead of rents being the primary driver of price the availability of land has become the primary driver.

However, from an institutional perspective this is not all that unreasonable. A manager must put capital to work in order to have a business. An investor wants a respectable return but is also looking at a land investment in his or her larger portfolio. Investors purchase land not for VC type returns but because they believe it to be like “gold with a dividend” – a safe place to store large quantities of capital which is inversely correlated with other markets. Further, the continued appreciation in land values has made up for the low annual payment from the asset. Many of these institutions have long holding periods which allows them to take advantage of any short term downturns in land and have greater appreciation over time.

Farmers, smaller funds, and local buyers often play in a different market all together. These transactions often happen over coffee in farm offices. Prices are never known and do not show up in any national reporting. Sometimes deals are done through local banks, sometimes owner financed and even occasionally done in cash. In terms of transaction volume these dwarf the larger transactions.

While these land purchases may have better cap rates than those bought by larger institutions, it is unlikely they will be far greater. However, for a farmer there are greater rewards for owning land. By owning the land she farms a farmer will have much greater returns over time by gaining the full upside of returns in good years and not sharing in upside with her landlord. Furthermore, there are times when a landowner may want a farmer to plant a crop that maximizes revenue (and rent to the landowner) instead of profit to the farm. A farmer can ensure the greatest level of profit by owning the land herself.

Aside from farm profitability a farmer’s future income benefits from owning land. Frequently, farmers retirement plan hinges on the land they purchase throughout their careers. They and their families depend on the rent generated from the land after they retire. Tax advantages through 1031 exchanges are available to individuals selling and purchasing new land and farmers take advantage of this frequently. They also have tax benefits such as being able to expense land improvements through their farming operation, thus lowering taxable profit to their farming operation while making capital improvements to the asset. Yet another advantage is being able to use the land as collateral for debt. Country banks are used to dealing with land as collateral and farmers are used to seeing it as a way to leverage their ability to expand their operations.

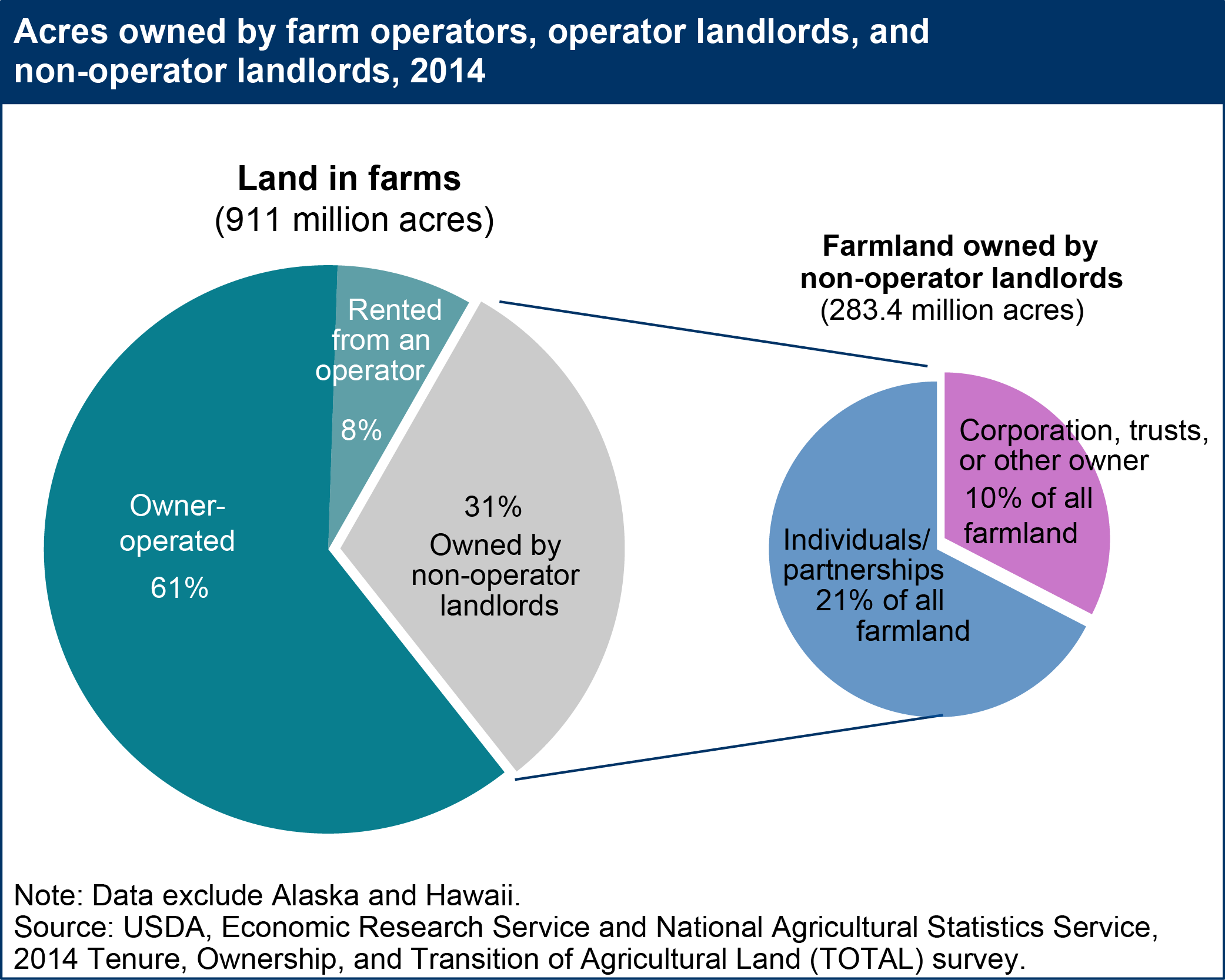

The size of these two markets is documented in a 2014 report by the USDA. While the data is a little old, it is still informative, and a few of their charts are worth highlighting to illustrate a few points.

While the chart above includes pasture land, it shows the amount of land owned by non-operator landlords. Of the 10% that is owned by corporations, trusts, and other owners, an even smaller fraction is owned by institutions. Corporations and trusts are often used by farmers to hold land intact when passing on to the next generation.

Slightly over half of all farmland is inherited or purchased from a relative. The remaining ~49% (it seems USDA may have some issues adding to 100%) remains for farmers, smaller investors, and institutions who purchase land from nonrelatives. If less than 10% of all land is owned by institutions, odds are low that they are purchasing much more than 20% of new land which comes to market in a given year. The transaction volume purchased by institutions is likely a fraction of that number.

Pricing

Pricing farmland much like most real estate is largely based on comparable transactions. Institutions have the best data on this. While they see a fraction of all transactions in the market they see far more than any individual. This is both advantageous and disadvantageous for the individual in the land market.

A farmer purchasing from an individual may have experience developing property and understand into what an undeveloped piece of land can be transformed. He may be able to get greater value out of the property by purchasing it at what it is today and turning it into something of much greater value to him or to institutions in later years. On the other hand, he may not understand the dynamics of how an institution works internally. If an institution does not believe there is a strong pool of tenants or does not have a strong land management infrastructure in his area, it may not pay top price that it would in other areas.

An institution bases its purchases on what it believes it can get out of the land in the long term. While it may accept low cap rates, it does understand what the potential cap rate and long term value of a property is. Institutions purchase assets where they believe that rent can be raised over time.

A Tricks of the Trade

Frequently a farmer will accept a higher price for his land and rent it back at a high rent. For the institution this locks in a high cap rate for the first few years, a basis for rent going forward, and a comp to value the rest of the portfolio. The farmer can take the profit from his land to be taxed as an investment and lower the profits from his farming operation over the last few years of his career to negate any tax liabilities he may have built up over his career.

Changes are a’comin’

In recent years land funds have grown bigger and bigger. This is great for managers of land funds who are able to collect substantial fees from the arrangement and still provide the services for which their clients pay them. However, investors are becoming more averse to large fees and interested in more investment. The market will likely demand to smaller funds and direct ownership of land for investors through separately managed accounts.

With direct ownership will come a greater interest in financial and operational reporting to investors for the individual asset. Institutions have some internal metrics but are unlikely to have the same quality of data as the investor’s managers of other assets. Larger amounts of data and transparency will be required not only from individual ownership but also as the industry continues to mature with investors and more money flows into the space. This desire for transparency will gradually be requested by individuals who are absentee landlords as well. What remains to be seen is whether the landowner, farmer or land manager will be responsible for the cost of collecting the data which will form the basis of the reports.

Problems Now and Later

Farmland is unlikely to switch to majority institutional ownership in the next 5, 10 or even 15 years. However, as the market transfers greater information about the asset will be required. This means that the inefficiency of the market will change gradually. In the meantime inefficient pricing will continue to be a burden for most participants.

This is true not only for what a property sells but also for what it can produce. There are many companies being formed and funded to try to understand what land has the potential to yield. However, we are a long way from knowing the potential of any individual asset. What may be possible is understanding what a tenant can produce on a given property with certain characteristics. However, farmers often guard their production histories or do not know the exact production on any given field. Getting this data from tenants is both burdensome and not the industry standard.

Land management and oversight by institutions and by third parties for other individuals will need greater transparency. It is impossible for any individual land manager to be on each of his properties every day. He cannot know if a property is being managed as he would expect. While in the majority of cases tenant farmer relationships are honest, there are cases where bushels or pounds of a crop produced by a tenant is reported incorrectly both by mistake and on purpose. This takes rent from landlords. There is no way for a manager to keep track of this.

Farm management in general is murky. There are few facts available to verify and it is highly reliant on farmers to be honest and managers to anticipate where problems may occur. While land manager performance itself is not to blame, the system itself is not up to investment standards in other industries.

Opportunities

Land investment today is one of the greatest opportunities for an institutional investor and a farmer or individual investor, because it is the most widely accepted form of farm investment. For the institution it is where the largest amount of money will be made in the near term. More and more investors are interested in the stability of owning US farmland.

For the smaller investor and farmer the fact that the market is inefficient offers opportunities for finding mispriced assets. A person with experience and connections can find land which will allow for well above average returns.

Even greater opportunity exists to aggregate tracts of property to sell to an institution. As mentioned before, an institution would rather purchase in large quantities to reduce the amount of time and due diligence required to deploy capital. This does require significant amounts of capital, but not as much as many institutions need to deploy. There is a middle ground here for smaller funds or individuals with the ability to aggregate a portfolio of properties.

For the investors or entrepreneurs interested in the industry but not owning land directly opportunities exist to provide transparency in the market. There have been a few groups to try this by creating two sided networks of buyers and sellers or to create platforms to have farmers keep track of data and sell it to others. These solutions are too far from where the market stands currently. The greater opportunities exist around helping with the process as it stands today. There is not only little information on pricing, but also there is very little about the transaction process. There is room to educate sellers on what will be one of the largest transactions of their lives. There is room to help them allocate the funds after having sold the land. There is room to help them understand different methods of selling their assets and what are the benefits of each transaction type and counter party. There is also opportunity to help land managers work with tenants by creating reporting standards and methods around the land and tenant, by providing a way for tenants to be transparent with their managers, and by decreasing the amount of work a manager must do on an individual property so he can manage greater amounts of land.

Farmland investment can seem out of reach for new entrants, but there are plenty of opportunities in which to invest both directly and tangentially.